- History of Museum

- Buildings

- Museum Quarter

- Departments

- Branches

- Administration

- Support us

- Documents

- Activity

- General Information

- Contacts

- Vacancies

- Terms of Use for Materials and Images

- Plan your visit

- Tickets & Privileges

- Buildings & Opening hours

- Guided tours

- Rules & Recommendations for visitors

- Accessible Museum

- Online shop

- Masterpieces

- Paintings

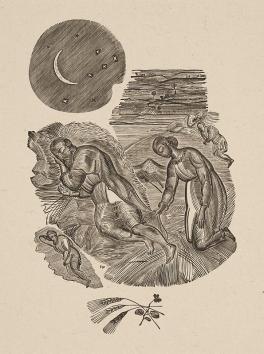

- Graphics

- Sculpture

- Applied Art

- Ancient East

- Art and Archaeology of Ancient World

- Numismatics

- Art Photography

- Casts Collection

- Electronic publications

- Online dictionary of photo techniques

- Virtual Pushkin Museum

- Electronic collections

- Accessibility

- Satellite websites

- Museum on other web sites

- Video channel

- Podcasts

- Audio&Media Guides

- Games and quiz

- 3D-reconstruction and modeling

- Virtual Exhibitions in Navigator4D format

- Smart Museum 3D

- Pushkin Museum XXI

- Contexts. Photographers and photography

- Attention

- Museum

- For Visitors

- Exhibitions & events

- Collection

-

Media

- Virtual Pushkin Museum

- Electronic collections

- Accessibility

- Satellite websites

- Museum on other web sites

- Video channel

- Podcasts

- Audio&Media Guides

- Games and quiz

- 3D-reconstruction and modeling

- Virtual Exhibitions in Navigator4D format

- Smart Museum 3D

- Pushkin Museum XXI

- Contexts. Photographers and photography

- Education & Science

Large font • contrasting colors • no pictures

© The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts